What comes to mind when you think of yeast? To a baker, it might mean the ability to make their dough rise. A brewmaster might associate it with the fermentation of beer and wine. Many others may associate these types of fungus with one dreaded infection or another.

Yeast serves many functions. For the University of Georgia’s Douda Bensasson, it’s all of these—and more.

An associate professor in the Franklin College of Arts & Science’s Department of Plant Biology, Bensasson uses yeast to unlock some of life’s greatest mysteries. Among the questions she seeks to answer is one concerning the fate of some of earth’s species. How will different species cope with the impacts of a warming climate? Will they adapt or go extinct?

“Some yeasts adapt well to different climates, while others don’t,” Bensasson explained. “In our lab, we are using that as our testing ramp to try and figure out what the rules are about which species make it and which species don’t, who is able to migrate and who cannot.”

In the lab, Bensasson and her team can finely control yeasts’ growing conditions, yielding illuminating results about a species’ ability to survive in a world where weather patterns are becoming more extreme and habitats are uprooted. The results could apply to other species that are difficult to study, such as endangered animals or plants, as well as other microscopic fungi.

Another area of rising concern is fungal disease in areas experiencing drastic climate change. To address these concerns, Bensasson has broadened her research into pathogens.

“This is a sweet spot for me,” Bensasson said. “I am well positioned to help in that area in terms of identifying some kind of warning system for new fungal diseases, for example, by using PCR tests to identify pathogenic yeast in wastewater, food or agriculture.”

‘Massive yeast envy’

These days, Bensasson works almost entirely with yeast. But that was not always the case.

She started her research on mountain grasshoppers, work that quickly posed several challenges. Although these creatures had once been widely researched, due to their large chromosomes that could be easily observed under a microscope, Bensasson found that they were very difficult to breed.

“It was like trying to breed panda bears,” she said with a laugh. “It was impossible to get them to survive and ultimately work with them.”

The grasshoppers were equally difficult to find in nature. Bensasson traveled to the Alps, one of their natural habitats, to collect samples for research, only to find that warming temperatures had driven them from areas in which they had been studied just 10 years prior.

Bensasson pressed on. Several years later, however, as a Fulbright Royal Society fellow at Harvard, she got the chance to work alongside scientists who were experimenting with yeast. Through these encounters, she admits to what she now calls “massive yeast envy.”

“I was in a lab with people working on yeast, and they were just there—trillions of them, living happily among themselves,” Bensasson said. “They are incredibly easy to work with, and we can control their growing conditions. We can control their climate with the push of a button. So, yes, they are much easier to work with than grasshoppers.”

A discovery decades in the making

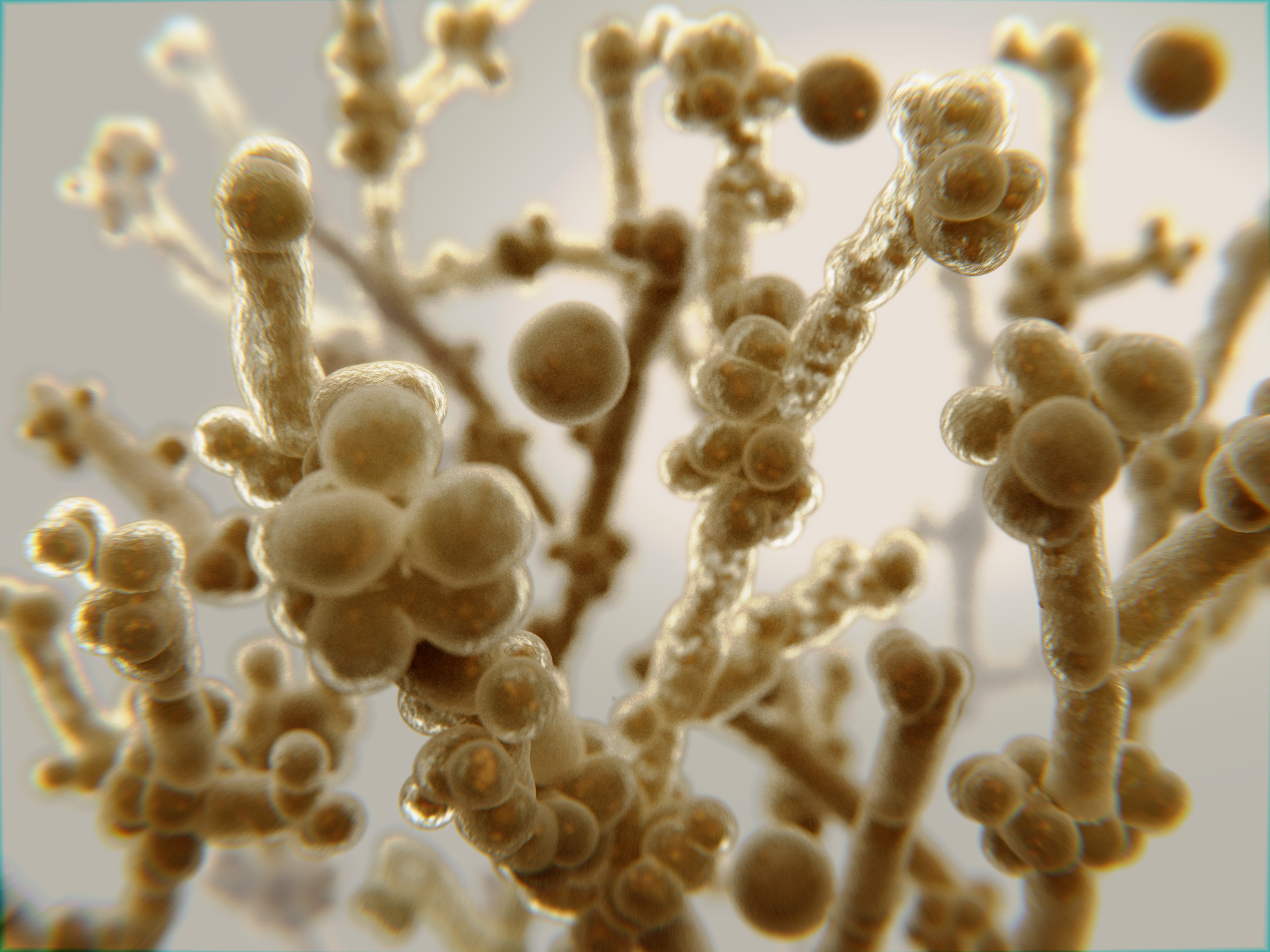

Throughout her career, one of Bensasson’s most significant discoveries involved the yeast species Candida albicans, which is responsible for a potentially lethal bloodstream infection in humans. Despite the danger it poses, C. albicansis extremely common. In fact, according to Bensasson, more than 50% of the population will have C. albicans living on or within them at some point during their lives.

“C. albicans is the biggest cause of hospital visits and death out of all the fungal infections,” Bensasson said. “It really does affect most people.”

It was previously thought that C. albicans could survive only within warm-blooded creatures, but Bensasson’s lab discovered that old oak trees could harbor the pathogen. Previous researchers had raised the possibility of these reservoirs going back decades, but their findings were dismissed as inadvertent human contamination of the trees.

Bensasson’s research was the first to prove conclusively that these trees do indeed harbor C. albicans, and although the risk of yeast infection from trees is effectively zero, it’s critical that scientists understand natural reservoirs of disease.

“When we first found it on trees, my colleague Michelle Momany was like, ‘Oh my gosh, you’ve got to prove that they really live there, because that’s going to shock everyone,’” Bensasson said.

The discovery that wild plant environments serve as reservoirs for common fungal infections like C. albicans has triggered other reports across the globe that corroborate these findings.

“It’s also exciting to find these natural reservoirs of the pathogens because they’ll have natural enemies there,” Bensasson said. “So, it’s potentially a place where we could search for new cures. We could find and research the enemies of our enemies, so to speak.”

In recognition of this exceptional finding, Bensasson was honored with the UGA Creative Research Medal in April 2022. She credits her colleagues for pushing her throughout the nomination process, particularly John Burke, head of UGA’s Department of Plant Biology, and Michelle Momany, a fellow researcher in her department.

“It means a lot to be so appreciated by my colleagues that they kept insisting on nominating me,” Bensasson said. “I love my research, so this was a true honor.”

Diversifying the next generation of researchers

Bensasson has not only been recognized for her research but has also for her stalwart efforts to diversify the next generation of STEM researchers. For her, diversity is not merely an interest—it’s a prerequisite to running any laboratory. Growing up in the United Kingdom as the daughter of Greek immigrants and learning English as a second language, she knew early on what it’s like to feel different. She has taken these experiences with her throughout life.

“I’ve definitely been in situations where I felt I didn’t belong,” Bensasson said, “so I just want to make other people feel they belong. If people can’t truly be themselves and be creative and flourish, then we aren’t truly tapping into the best science.”

Bensasson has worked to identify tactics that can be used to stimulate an inclusive laboratory environment, including racial and gender equity. An additional problem in STEM, she said, is that undergraduate students with research experience are sometimes favored over those without it, disadvantaging those who come from marginalized backgrounds.

“Another one of the barriers I’ve seen is students thinking by the time they get to grad school, they should have all this experience in computing,” Bensasson said. “They think they’ve missed out—but they haven’t. That’s what grad school is all about: picking up new experiences.”

In order to overcome these barriers, Bensasson does not require undergraduate researchers to have prior research experience in order to join her lab, or graduate students to have computing experience. She also champions paying student researchers so that students of all economic backgrounds can participate.

As a testament to her convictions, Bensasson was recently awarded the Gilliam Fellowship for Advanced Study from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, alongside UGA graduate student Jacqueline Peña. This award is meant to ensure that students from historically marginalized groups are prepared to assume leadership roles in science and scientific education, and to foster the development of a healthier, more inclusive academic ecosystem within the sciences.

“I have learned so much through this award about supporting students that face microaggressions, systemic biases and just being a better mentor generally,” Bensasson said. “It’s really taught me a lot of things I strive to implement in my own lab and life.”